Editor's Note: This research brief is part of a joint research project by the Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy at The New School and Brookings Metro.

Chicago Pioneers Equity Impact Assessment in Affordable Housing Development

Chicago’s role as a racially and ethnically diverse economic powerhouse and its reputation for bare-knuckled politics and persistent neighborhood segregation, have long put it in the spotlight among reformers in the movement for racial and economic justice. But few outside the city’s public life are familiar with the remarkable set of efforts by leaders-in both civil society and government-and from grassroots neighborhood groups to a regional leadership council, to embed equity impact analysis into a range of public agencies. Agencies whose decisions affect the city’s residents, and especially its communities of color, on a daily basis.

From public schools to affordable housing development, progress has been hard won and full of lessons, extending across several mayoral administrations and counting. The nation’s first-ever adoption of racial equity impact assessment by a housing agency was announced, (and as we highlighted in our fall report), when the City of Chicago’s Department of Housing released its Qualified Allocation Plan for federal low income housing tax credits in 2021. The plan provides an intriguing and revealing window into a much larger story.

To date, there are several important lessons learned from Chicago’s efforts so far. First, equity impact assessment can provide civic and social movements for fairness and justice with a valuable mechanism for operationalizing the change they seek and to promote continued public learning about what change requires in concrete terms. Second, the capacity building that is so important for producing credible equity impact assessment, not to mention translating them into tangible outcomes that matter, can usefully include civil society and public sector leaders, and benefit from the circulation of committed, skilled talent between the sectors. This was another major theme highlighted in our first report.

Chicago’s experience is a reminder not to think of these capacity improvements as being a simple, linear story of community advocacy or outside pressure producing an isolated “inside game” of changes within government agencies (as critical as those are). This is especially true in an area like housing and community development, since it relies on a “hybrid” delivery model, working through nonprofit and for-profit actors such as real estate developers, rather than direct service provided solely by public agencies. But third, and corollary to that hybrid public/private delivery point, Chicago’s experience makes clear that effectively framing the purpose of adopting racial equity impact assessment, or equity scoring, matters for getting results in and through agencies tasked with implementation–and that is critically different from, say, the relatively internal, staff-centered focus of much diversity equity and inclusion (DEI) work within organizations. It is also reflective of what we referred to in our first report as the generative quality of impact assessment done well: serving not only to highlight the stakes in public policy decisions more clearly but suggest new solutions as well.

Those distinctions–especially between DEI work to change the internal workings of a public agency and REIA-driven work that focuses on changing the agency’s impact on those it serves–are crucial, for communities, leaders, and civil servants. Now three years past the mass protests for racial justice in the summer of 2020, efforts to secure change are confronting greater resistance to the very public and high-profile commitments announced by so many.

We do not suggest that REIAs offer a panacea or an easy path through hard conversations, let alone concerted political backlash. But Chicago’s experience points to some specific ways that change efforts can take advantage of the old adage that sometimes one should “show, not tell.” As illustrated below, the push to implement change has leaned heavily on continuous refinement and the trial of new approaches to agency program delivery–more than high-profile policy announcements. In that sense, the experience represents, in some ways, the opposite end of the spectrum when compared with the very public controversies and contestation that attaches to major local land use reforms–and the real estate mega-projects they are often spurred by, like those described in the New York City case.

The arc of a civic movement for equity and justice in the Chicago region

It has often been observed that movements for change need both the grassroots and the grasstops. Without the former–the energy, commitment and voice of everyday people finding common cause and acting on it–advocacy is often short lived and weak, not to mention inauthentic. But likewise, unless change agents with a grassroots base of support are able to cultivate allies who have the access to resources and authority, movements struggle to convert popular energy and demands into lasting institutional change. The activism of the 1960s ,inspired by and modeled after the civil rights movement, produced a pointed shorthand: One vital part of the work of social change is going “from protest to proposal.”

In Chicago, where generations of work to advance racial and economic justice converge with very immediate and ever-evolving targets for civic organizers to engage with vulnerable communities has been no exception. In 2016, two Chicago activists–Niketa Brar and Elisabeth Greer–served on their local school council. The two got to know each other and began to discuss what it would take to advance real and lasting equity in public education, andThat conversation would prove very timely. The following year, Chicago Public Schools announced plans to close National Teachers Academy, their successful elementary school, which displaced its mostly Black and low-income students.

In the effort to organize community opposition and create alternatives to that government proposal, Brar and Greer founded Chicago United for Equity (CUE). The organization would soon pioneer the use of racial equity impact assessments, REIAs, in Chicago to ensure a more thorough and legitimate analysis of the stakes of such policy proposals, and present innovative and community-informed alternatives. These REIAs turned out to be not unlike the trailblazing, nongovernmental “community plans,” (sometimes called “counter-plans),” catalyzed by the protests over proposed highway and other controversial projects funded by the federal urban renewal program half a century ago.

As the CUE website explains, “The art of making policy is in finding solutions to community problems. Yet so many of our solutions come with new harmful effects. Too often, that harm is repeated on communities of color. To interrupt this cycle, over 125 government bodies across 30 states have adopted a Racial Equity Impact Assessment (REIA). This tool weighs the benefits and burdens of a new idea to protect against new harm. We believe that Chicago must adopt this tool to promote racial equity in the decisions leaders make every day.”

CUE produced its first REIA–the first in the region–to question the proposed school closure and went on to produce others centered on the use of taxpayer resources to fund major real estate projects, transportation policy proposals, and other significant proposals. In fact, all of CUE’s REIAs use the basic structure and method developed by Race Forward’s Government Alliance on Race and Equity, and are publicly available here. Many leaders across the city, including one who would soon become the city’s housing commissioner, had the opportunity to experience a REIA development process for the very first time ever,and described it as powerful.

Another note on CUE’s growing presence and impact: The organization did more than produce REIAs about specific policy proposals, it built out a strategy for change with three mutually reinforcing elements:

- Build a network of ethical and effective racial justice advocates across Chicago’s civic infrastructure

- Demonstrate tools and models for equitable policies and practices

- Develop citywide public accountability models for racial equity

“We believe there are three types of power crucial for doing this work,” says Brar, CUE’s co-founder and executive director, “the policy making power of lawmakers and other public officials, the mobilizing power in communities, and the narrative power of research institutions, news media, and philanthropy, among others.”

In the same year that CUE began the campaign to respond to the proposed school closure, another regional organization with decades of work in housing and economic development began to advocate for the adoption and use of REIAs by public agencies. In 2017, the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC), a nonpartisan civic organization founded in 1934 to help shape development throughout the Chicago region, published a landmark report, The Cost of Segregation. It highlighted, among other costs to the region’s residents and employers, “billions in lost wages, thousands of young people without the education they need to fulfill their potential, hundreds of lives cut short by violence.”

Crucially, the 2018 follow-up report, Our Equitable Future: A Roadmap for the Chicago Region, called for the use of REIAs by public agencies, as a means of reducing segregation and its costs and promoting more equitable development of the region. MPC collaborated with CUE to produce the report. The election of a new mayor would soon offer an extraordinary opportunity to act on that recommendation.

Creating the nation’s first-ever REIA for affordable rental housing development

In April 2019, Chicago voters elected Lori Lightfoot mayor–the first Black woman and first openly gay person to hold the office. For housing commissioner, Lightfoot appointed Marisa Novara. A former neighborhood housing developer on the west side of Chicago, Novara was then MPC’s vice president, led its ambitious Cost of Segregation and Our Equitable Future reports, and participated in CUE’s community process to produce the first REIAs in the city.

In April 2019, Chicago voters elected Lori Lightfoot mayor–the first Black woman and first openly gay person to hold the office. For housing commissioner, Lightfoot appointed Marisa Novara. A former neighborhood housing developer on the west side of Chicago, Novara was then MPC’s vice president, led its ambitious Cost of Segregation and Our Equitable Future reports, and participated in CUE’s community process to produce the first REIAs in the city.

Novara saw an opportunity to put the MPC/CUE REIA recommendation into effect. The federal government requires that Chicago, like other jurisdictions, submit a “qualified allocation plan” for the use of Low Income Housing Tax Credits. LIHTCs (“lie-tecks”) are the country’s largest capital source for developing or rehabilitating affordable rental housing. LIHTCs are mostly invested by state housing financing agencies, but a handful of large cities, including Chicago, receive allocations directly from the federal government. What if Chicago were to use the process of developing its QAP to think through the range of choices that go into developing projects, situating them in neighborhoods across the city, generating business opportunities for private for-profit and nonprofit developers, and screening and serving eligible tenants–all of it with the racial equity impacts of those choices, and possible alternatives, in mind?

So began the effort to create the nation’s first-ever REIA for affordable housing finance and development. But there was no roadmap for doing so, and Novara’s agency, the Department of Housing, had limited capacity to do so effectively on its own. So CUE lent assistance, through a competitive fellowship program that–as a core element of CUE’s three-pronged impact strategy–was training a rising generation of practitioners to understand and use REIAs. Katanya Raby, a CUE fellow then working in the Mayor’s Office, joined Commissioner Novara and her team. Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit technical assistance organization with deep experience in affordable housing finance and development across the country, also engaged to help.

Novara and her team reviewed the city’s QAPs going back two decades to gauge the results those plans had and had not produced. The team also identified the groups of stakeholders most critical to engage in the planning process, including residents of the LIHTC-financed housing developments, the real estate developers who designed and completed the projects, and housing and community development advocacy organizations across the city.

But effectively engaging agency staff–a core theme of our first report on the evolution and application of REIAs across the country–was critical too. As Commissioner Novara recalls, there’s an understandable tendency for professionals driven by their mission to think, “this is about our personal attitudes and becoming antiracist” as opposed to “this is about examining our core programs and functions to determine to what degree our outcomes are racially equitable.”

The leadership team emphasized that the assessment would not be a referendum on individual staff members or their dedication to the mission but a careful analysis of outcomes the program was or was not achieving, regardless of staff intent. Emphasizing the opportunity the REIA-centered planning afforded the agency, the planning team worked steadily to take advantage of what Katanya Raby calls the “amazing skills and experience” of Department of Housing staff, especially their practical knowledge of how to get ambitious goals implemented.

After months of stakeholder engagement, analysis, and option development, the department released its draft QAP in March 2021 and invited comments before it then finalized the plan (Racial Equity Impact Assessment: Qualified Allocation Plan 2021). In it, the city announced its intention to use eight new goals to guide the development of affordable rental housing financed by LIHTC. These included specific changes to tenant services, a stronger commitment to equitable siting of projects across the city, and a concerted effort to expand opportunities for Black and other traditionally under-utilized developers who got LIHTC business from the city.

The new QAP drew positive reactions from the advocacy community and considerable local media attention–for what had long been a relatively obscure and technical government document.

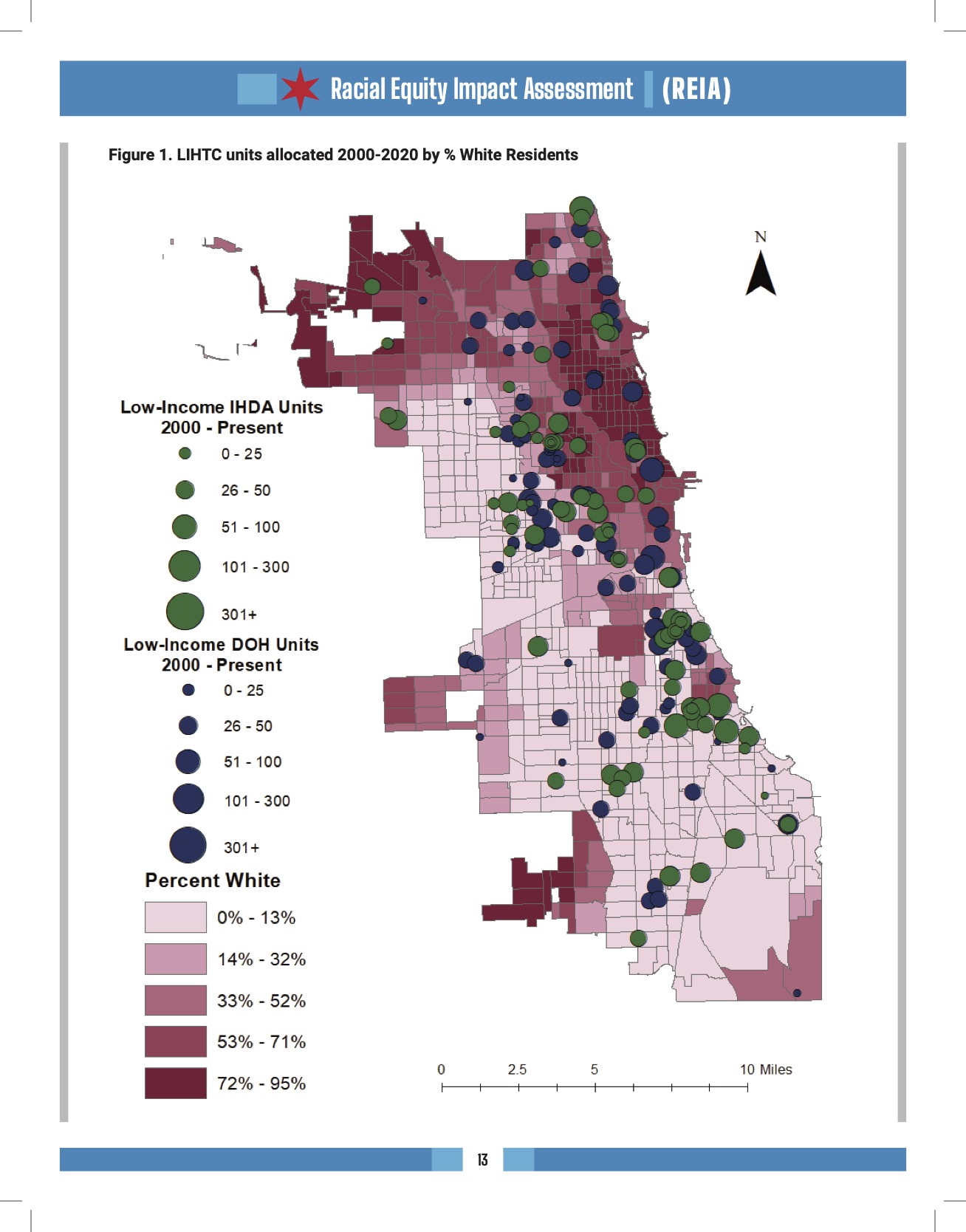

Coverage from NBC News underscored the finding that LIHTC developments had, over the prior decades, overwhelmingly been sited in Chicago’s poorest Black neighborhoods, reinforcing the city’s deep and persistent segregation, and isolating residents of government-supported affordable housing from safer streets, high-performing schools, healthy food, and other essentials for wellbeing and opportunity. Sadly, this mirrored a long-documented national pattern for the LIHTC program. National trade media in affordable housing likewise broke the news that “Chicago Changes How It Allocates Tax Credits,” and soon after covered efforts by other housing finance agencies to replicate the Chicago approach in other parts of the country.

Taking stock, and raising the bar

Based on the innovative nature of the 2021 QAP, the Implementation of the tax credit program has produced measurably different results in Chicago, evidenced by who can develop affordable rental housing projects, how, and where in the city.

During the 2021 round of tax credit award for example, the housing department supported 24 affordable housing developments in 20 areas of the city. Unlike the past however, the department managed to invest in all three of its target neighborhood categories: Low-income, historically disinvested; gentrifying and transitional; and more opportunity-rich (which tend to be higher income). In addition, Chicago enacted a transit-oriented development (TOD) ordinance in 2013 to encourage denser housing development near transit stops, whereas prior to the 2021 QAP, 90 percent of the developments that took advantage of the new TOD incentives were in higher-income neighborhoods.. After the QAP, the developments in that round of 24 were 75 percent TOD projects, and two-thirds of those were in low-income, disinvested communities.

Because previous QAPs had been race-neutral, the department did not possess hard data on its housing developers, but estimated that the vast majority of those awarded LIHTC in the past were white-led. In 2021, by contrast, after calls were made for teams that were BIPOC-led or a joint venture, 12 of the 24 awarded developers met that qualification. The department is also expected to further expand BIPOC representation as more firms gain capacity.

Finally, that first REIA in 2021 was no one-off: Chicago updated its qualified allocation plan this year and made some goals even more specific and ambitious. In that vein, this case illustrates the generative quality of carefully executed REIAs. For example, asking “what would it take?” to make major progress on investments via Black and other developers of color has generated a bigger push for supplier development, i.e., expanding the pool of developers able to bid successfully for LIHTC funding, including new financing solutions for chronically under-capitalized small developers.

To be sure, major challenges remain for Chicago communities and the agencies that serve them. The equitable and geographically inclusive siting of projects remains hard in a sprawling, segregated city with divergent trends between neighborhoods. Depopulation is also still happening in many of the city’s fifty wards while in-migration of higher income households–and accompanying gentrification and displacement–is a flashpoint in others.

Chicago’s work to produce the country’s first REIA for affordable housing finance development did not arise in a vacuum. It was part of a broader civic movement that engaged the grassroots and grasstops, training and deploying rising leaders to be effective advocates for racial equity with knowledge of the REIA tool specifically, and linking the use of REIAs to a local imperative-to bring significant new commitment and resources to reduce the “hypersegregation” of Chicago, as some longtime analysts have noted. It is a very persistent pattern of inequality by race, income, and geography that imposes the greatest harms on the nation’s most vulnerable people–but ultimately costs us all significantly, as MPC’s seminal 2017 report made all too clear.