By Madeline Brown | August 26, 2024

Baby Bonds are an increasingly popular bipartisan government policy in which every child born into poverty receives a publicly funded trust account at birth. This “start-up capital” allows young adults to access education, home ownership, and entrepreneurship, enabling them to build wealth and lead lives that are hopeful, fulfilling, productive, prosperous, and self-directed. Follow our Baby Blogs series to learn about the vision, politics, and people behind Baby Bonds and their transformative impact on the lives of young people, their families, communities, and our economy.

In this installment of Baby Blogs, Madeline Brown, senior policy associate at the Urban Institute, shares her talking points for describing Baby Bonds in the context of current racial wealth inequities to the public and to new and potential stakeholders.

In the spring of 2022, fresh off big legislative wins for Baby Bonds in Connecticut and Washington, D.C., my Urban Institute colleagues and I began convening experts on wealth equity to support the offices implementing these programs. Between 2022 and 2023, eight more states introduced Baby Bonds legislation, and the group grew. What started with a request from state treasurers evolved into an engaged group of experts, practitioners, and policymakers, who, among other accomplishments, came together last October to lay out a set of principles for a federal early-life wealth-building policy.

My colleagues and I have published much of what we’ve learned so far on this work, including a legislative update, literature review, lessons learned on building public support, and findings on the relationship between the source of funds and the target sums we all hope these accounts achieve. We’ve testified in D.C. and Massachusetts, and served on both the CA HOPE Accounts and Massachusetts Baby Bonds task forces.

My biggest lesson learned in all of this is that we have to talk about wealth differently—and we must be clear about what parts of wealth inequality Baby Bonds can, and cannot, solve.

When I talk to media, consultants, or anyone new to this policy, there is an inevitable level setting to be done before I can get into the details of the policy. Here are my most-used talking points in the hopes that they are useful for you, too.

Wealth isn’t just for millionaires.

Everyone deserves to be able to weather an unexpected medical bill or car repair—and yes, to have the opportunity to purchase a home, invest in a business, or go to college. Yet in 2022, only about half of households (51 percent) in the U.S. had emergency savings equal to at least one month’s income. Assets like homes and retirement accounts can be leveraged in tight times, but in 2022, white families had about $260,000 more in average retirement savings than both Black and Hispanic families, and had homeownership rates 23 percent higher than Hispanic families and 29 percent higher than Black families. When I talk about Baby Bonds, I don’t suggest that everyone has a right to be a millionaire, but everyone should have the same opportunity to build wealth and resilience for their families.

You can’t earn and save your way out of structural racism.

The data show us that you can’t earn or educate yourself out of the compounding influences of historical and structural racism. Last April, we published updated charts on wealth inequality in America. We use this feature to try to make wealth distribution data accessible for a broad audience—and to identify the main drivers of wealth inequality. We have insightful figures on emergency savings, retirement savings, tax benefits, homeownership, intergenerational transfers, and earnings. But the number that gets cited the most? In 2022, the typical (median) white family’s wealth ($284,310) was 4.6 times that of the typical Hispanic family ($62,120) and 6.5 times the wealth of the typical Black family ($44,100). And we’re talking medians here, ignoring the ultra-wealthy for a moment—who hold 71 times the wealth of families in the middle, and who are also mostly white.

Baby Bonds won’t solve distributional inequities, but they can provide capital at a critical point in the life course.

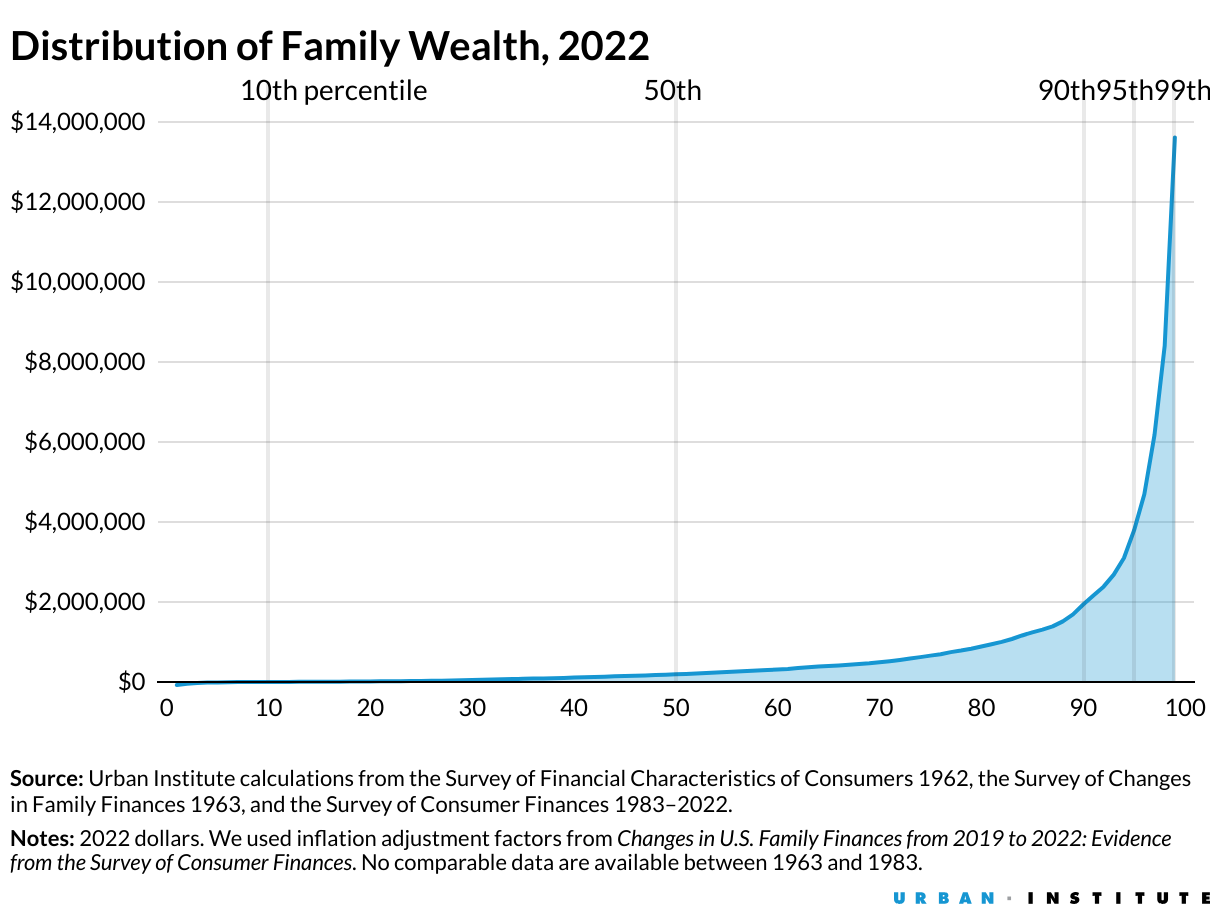

In the past 60 years, America witnessed a massive transfer of wealth from the middle class to the wealthiest families, increasing wealth inequality. Our longitudinal wealth distribution in this country looks like a standard exponential growth chart (see figure below).

The target sums of most Baby Bonds proposals are somewhere between $3,000 to $10,000 on the lower end and $40,000 to $50,000 on the higher end. These sums won’t re-configure the wealth distribution curve, but they offer a crucial lever for asset-building for the next generation. Racial wealth inequities are smaller in early adulthood than later on because wealth attainment over a life course occurs both as financial assets appreciate, and various opportunities arise or not (homeownership, employer-sponsored retirement savings matches, etc.)—and these opportunities do not occur randomly. Indeed, scholars argue wealth attainment is a consequence of the accumulation of racial discrimination. Thus, if we can introduce capital, seeded progressively, when inequities are smallest, we can set up entire generations of young people to see meaningful appreciation over their lifetimes.

Making Baby Bonds a reality in all U.S. states will require effective communication about the policy. This includes not only an honest look at how wealth is distributed and accumulated in the U.S., but also the essential role it plays in determining an individual or family’s agency and resiliency. Baby Bonds and other asset-building tools are more than just economic policy; they are rooted in a fundamental commitment to human rights and well-being.

Madeline Brown is a senior policy associate in the Research to Action Lab at the Urban Institute, where she promotes racial equity and inclusion in local, state, and federal policy. She currently focuses on financial security and the racial wealth gap, developing timely products, growing the evidence base, and leading technical assistance to inform policymakers and practitioners. Her work also includes the policy domains of housing, civic participation and representation, broadband access, and workforce development and examines the ways these systems were shaped by structural racism. Before joining Urban, she worked at FairVote, a nonprofit focused on U.S. electoral reform, providing research and analytical support.

If you missed previous installments of our Baby Blogs series, read them here.

To share feedback on this blog, or for questions about Baby Bonds, email David Radcliffe at radclifd@newschool.edu.

To learn more, explore our Baby Bonds resources.