By Mary Schmidt Campbell, PhD, President Emerita, Spelman College

(Originally presented as a lecture at the New School December 1, 2023)

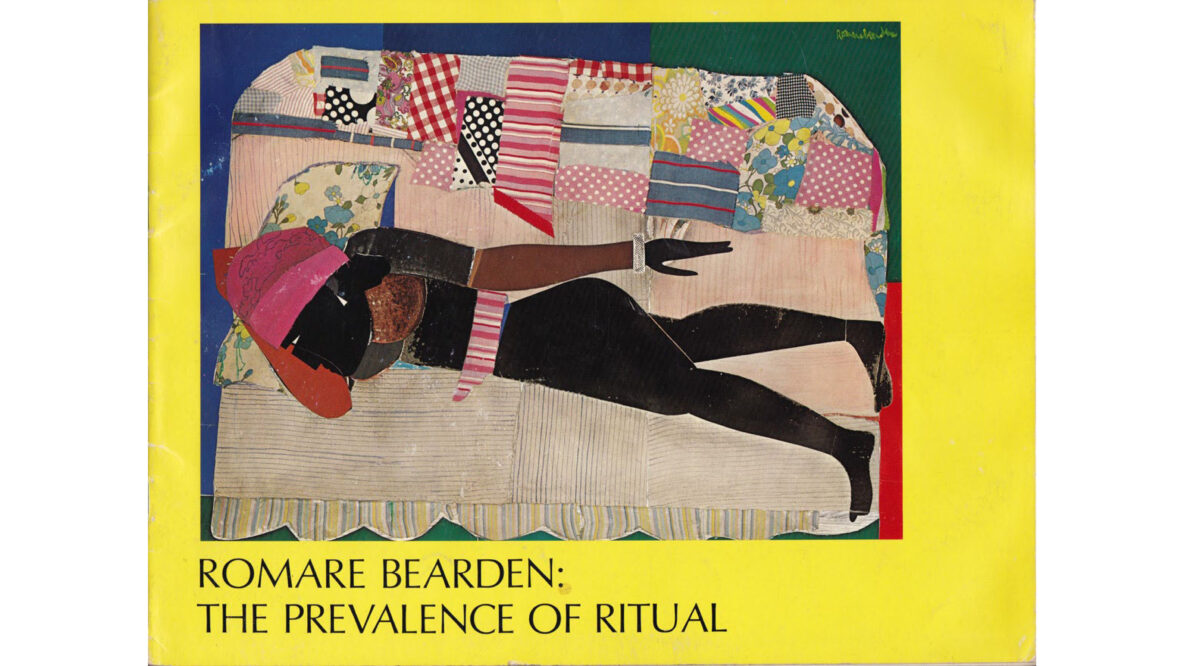

Romare Bearden’s artistry first revealed itself to me in a retrospective that landed at the Studio Museum in Harlem during the summer of 1972.[i] The show and its unscheduled stop at the Studio Museum were the result of energetic political activism, much of which Bearden wholeheartedly endorsed. New York’s Museum of Modern Art, at the time, the supreme arbiter of twentieth-century modernism, had mounted Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual, a year earlier, the first ever retrospective of his work at a major New York Museum. The Prevalence of Ritual was mounted at the same time as MoMA’s retrospective of the Black sculptor Richard Hunt; it was the first time the museum presented solo exhibitions of any Black artist in almost three decades. Protests organized by the Art Workers Coalition (AWC), especially Black artists Tom Lloyd and Faith Ringgold, who formed a Black caucus within the AWC, targeted MoMA’s then exclusionary exhibition and collecting practices[ii] American museums, in general during the 1970s and 1980s, were being taken to task by activists for excluding women and artists of color.

Fierce political activism might have brought the Hunt and Bearden exhibitions into being, but it was that of Bearden, personally, that brought his show to Harlem. As the national tour of the exhibition came to an end, Bearden insisted that the final stop be in Harlem, where he spent a part of his childhood and came of age as an artist. Harlem had been his home at a time when the community was incubating any number of great artists, masters of jazz, and world class visual and literary artists, as well as nurturing a consequential political voice. Decades after the Harlem Renaissance, Harlem in the 1970s was making every effort to reclaim that, once lost, cultural and political primacy. Bearden was unstinting in his support. His political activism is core to the legacy he has bequeathed to any number of artists, who have decided that their practices include accountability to a community, however that community might be defined.

As a graduate student studying art history, I was urged by my thesis advisor, a renowned Picasso scholar, to see The Prevalence of Ritual at the Studio Museum. An embryonic institution that opened in the fall of 1968, with assistance from the Junior Council of the Museum of Modern Art, the museum had as its mission the exhibition and interpretation of the art of the African Diaspora. Its physical presence did not quite match its institutional ambitions. In place of the massive stone structures that housed major museums, the Studio Museum’s space was a 10,000-square-foot loft over a fast-food restaurant and some retail shops with a decidedly uninviting entrance.

My husband and I entered the museum by climbing a dark, narrow stairwell, greeted at the top by spacious galleries, filled with Bearden’s collages, prints, Projections series, paintings, and drawings. To enter the space literally was to walk out of shadow, into a radiant sunlight of images that opened our eyes to the beauty of a world we had taken for granted. Bearden understood that housing the retrospective in a museum in Harlem, created expressly for the art of the African diaspora, albeit in a modest space, would feel like a radical act of affirmation and re-definition. Beyond the location, the work itself was unabashedly political.

Bearden often argued, strenuously, against viewing his art as a political statement. He constantly stressed his attention to form, composition, the chromatic harmonies and dissonances in the work. He was absolutely correct in doing so. Aesthetically, the collages on view at the Studio Museum needed no political justification; yet, ironically, at every turn, I found their politics on brazen display. The show opened with his early 1930s and 1940s, realistic representations of Black life during the Depression years, and charted the evolution of his work from realism to figurative abstraction. (For some reason, the “retrospective” overlooked Bearden’s monumental non-figurative abstractions that immediately preceded the collages.) In the figurative abstractions, Bearden turned to biblical themes and classical literature, what he called universal themes, executed in a cubist-derived style. The bulk of the exhibition, however, concentrated on his use of the medium of collage, which he began exhibiting publicly from 1964 to his death in 1988. Despite his resistance to being labeled an artist with a political agenda, he had discovered a way to make a profoundly political statement about the aesthetics of seeing, remembering, and knowing.

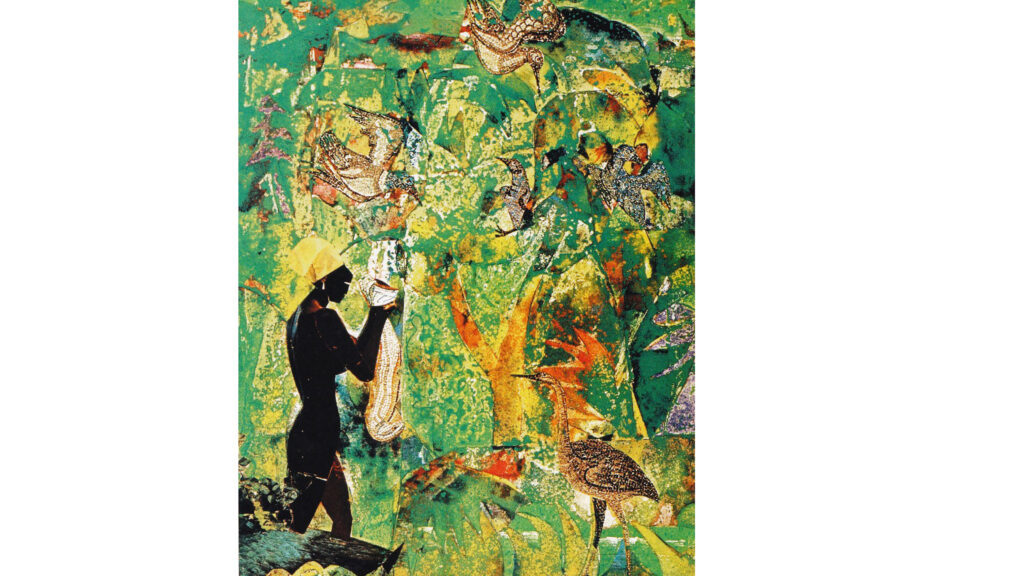

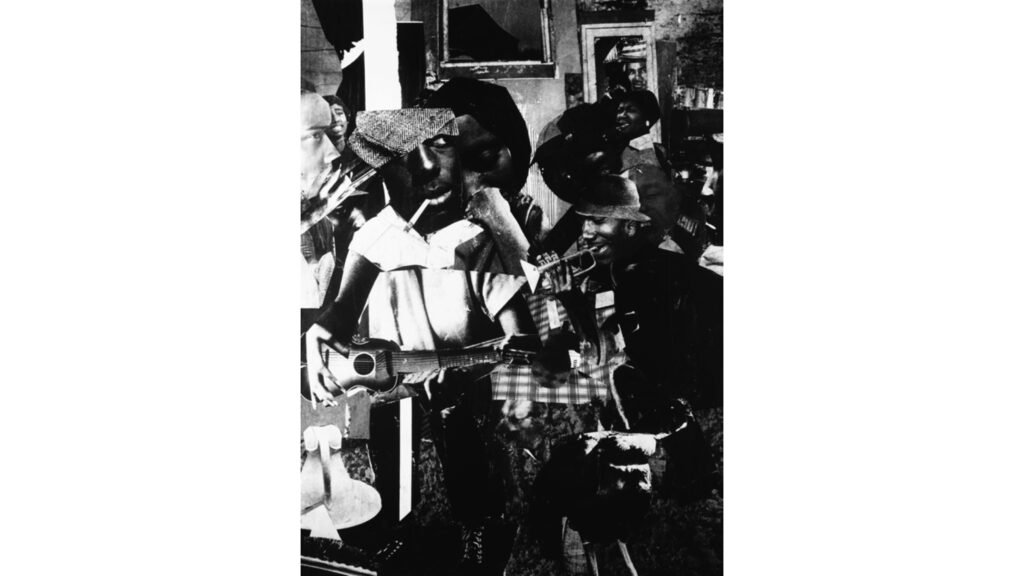

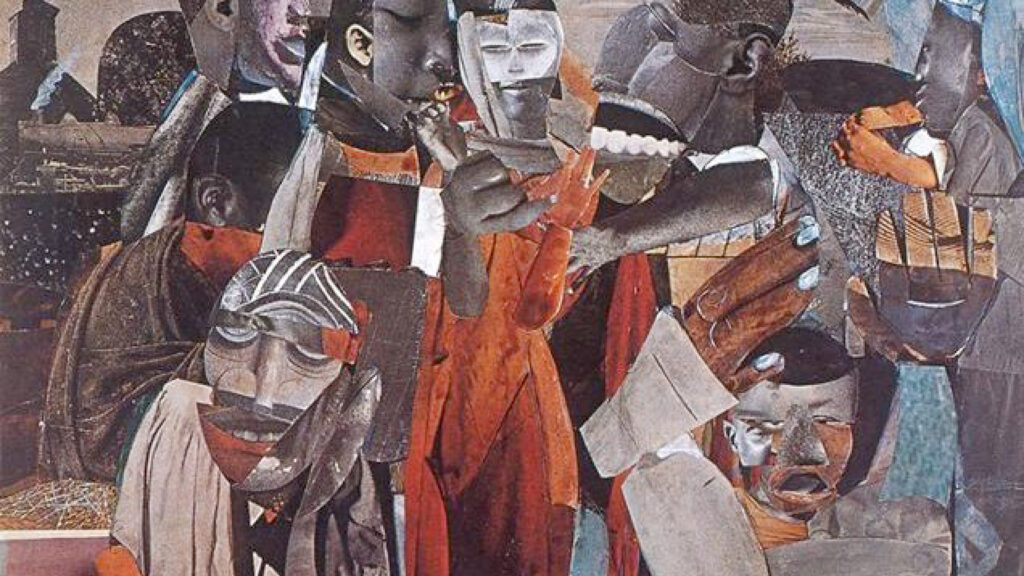

Whether it was a small, intimate, be-jeweled collage made of sliced bits and pieces of images cut from magazines, patches of brightly colored paper and paint, like Byzantine Dimension (figure 2) or a Projection, like Train Whistle Blues (figure 3), a black-and-white photographic blow-up of a collage, the images were authentic. That authenticity was evident at every turn. He could move effortlessly from the dazzling surface of a collage like Byzantine Dimension to the compressed space of Train Whistle Blues as congested and densely packed as a NYC subway. Bucolic, sensual imagery in some of the collages contrasted sharply with emotional agitated intensity in others. Bearden was emphatically denying unanimity in the representation of Black culture, ironically, even as he was insistently asserting the existence of richly sourced, yet distinctive Black culture.

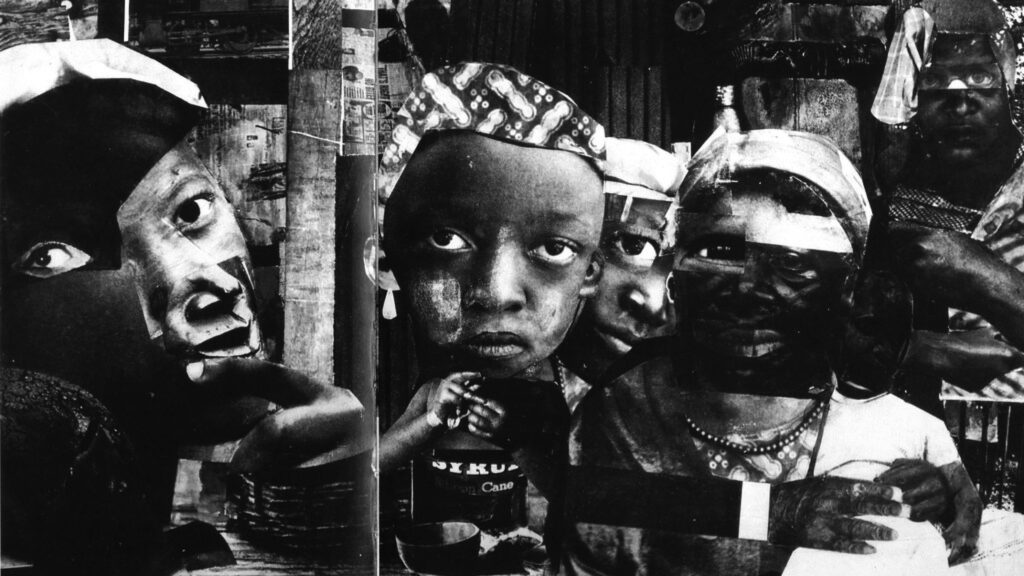

What was perhaps even more striking was the way in which the Bearden was shifting the relationship between spectator and subject matter, as if he wanted to call our attention to the dynamic of the powerlessness of being the observed vs. the power of the observer. In more than one Projection, he turns the faces of the Black inhabitants of his Projection directly to the viewer. Faces are pressed close to the picture plane, as in Pittsburgh Memory, or Mysteries, or The Street where the Projections’ subjects look out at us unflinchingly (figures 4–6).

Looking at those works as a young graduate student, I saw the streets, where I lived, the defiance and self-possession of the residents. I saw the rituals my family performed, the baptisms and family meals presented in a visual language that connected itself to world history (figure 7).

In portraying scenes that were recognizable and familiar, Bearden drew not only from images of Black life but from ancient Benin sculpture or sixteenth-century Flemish painting. He had not only taken complete ownership of the modernist ethos of collage, disrupted and revised it, making it his own, but he also felt free to plunder the treasures of Malraux’s global “museum without walls’ in order to show us what we could not otherwise see. He made the practice of art history feel as imperative to change as the call for new legislation or the winning of court cases. His audaciousness was liberating to a young scholar.

Audaciousness and liberation, fundamental to Bearden’s legacy, were evident in the work of the artists assembled on the occasion of the symposium, In Common: Romare Bearden and New Approaches to Art, Race and Economy.[iii] Whether it was the meditations on Matisse or Manet in Mickalene Thomas’s paintings of Black bodies, or the layers of time represented almost “archaeologically” in Hank Willis Thomas’ work, or the nonlinear approach to time represented by Lorraine O’Grady, hints of Bearden’s influence are present. Bearden’s honest embrace of modern urban life resonated in the work of Charisse Pearlina Weston and Kahlil Robert Irving; both heir to Bearden’s grasp of the cadence and pace of city streets. The dynamics of Black Quantum Futurism resonates with the kinetic energy of Bearden’s most potent Projections.

Fifty years ago, when I first encountered Bearden’s work, what I didn’t know at the time was how long and how far Bearden had to travel as an artist to arrive at his use of collage and his brand of modernism. How did he come to embrace the conceptual framework of The Prevalence of Ritual. That frame freed him from the orthodoxy of unyielding political statements, without sacrificing the ability to make searing political commentary. Bearden once referred to the distance traveled as an artist as a “Voyage of Discovery.”[iv] How he embarked on that voyage, where it took him, the obstacles he encountered, and his homecoming are the subject of this essay. When he set sail on his artistic voyage, as an emerging artist, during the Depression, he was an unabashed Race Man. After serving in the Army during World War II, by mid-career, his certainties about art and race had fractured and his “Voyage of Discovery” sometimes careened into tempestuous waters. Bearden’s interest in The Odyssey, charting Odysseus’ perilous voyage home, became a favorite theme in his late work.

The Unabashed Race Man

Bearden’s childhood was spent mostly in a Harlem, in a household where politics held center stage. The Harlem to which the Bearden family moved from the Tenderloin district in the early half of the twentieth century was home to highly curated, visually stunning political protest. An early example is the 1917 Silent Parade of 10,000 Black people. Women and girls, dressed in white with gloves and hats, paraded behind men and boys; the men in suits and straw hats marched silently. They held aloft placards announcing their complaints against an unrealized democracy, to the sound of muffled drums, as they marched. James Weldon Johnson, one of the organizers, reported on aesthetics of the parade in his column in The New York Age (figure 8).[v]

Two years later, the New York Times reported on the Harlem Hellfighters, the regiment of Black veterans, World War I heroes, whose return from Europe was celebrated with a parade from Madison Square Park to Fifth Avenue, accompanied by James Reese Europe’s band. [vi] Bearden remembers the visual pageantry of a host of parades, including those of Marcus Garvey, which carried the message of Black repatriation, dramatically promulgating his aspirational dream of returning Black people to Africa (figure 9).

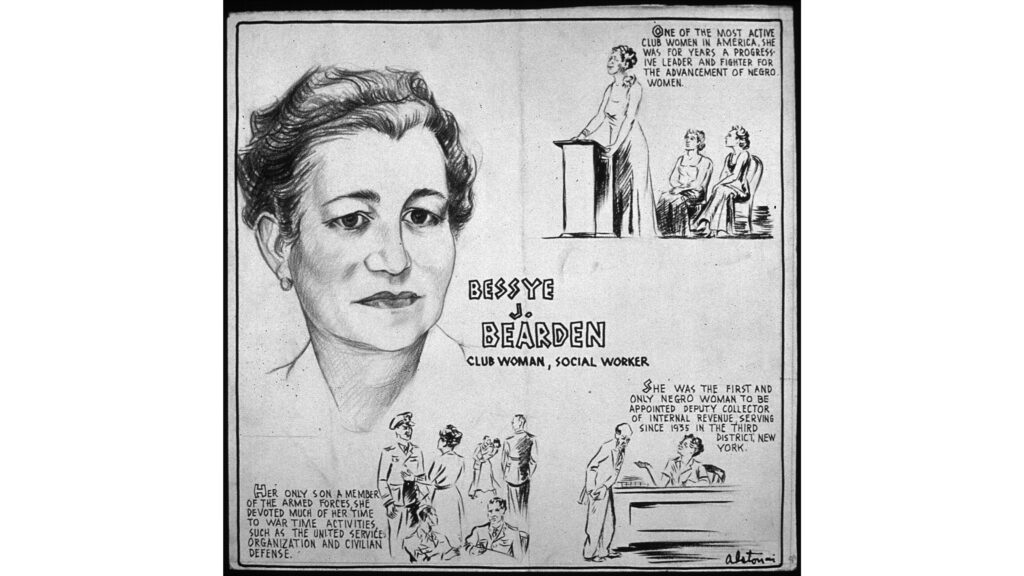

Closer to home, Bearden’s mother, the formidable, Bessye Bearden (figure 10),assumed a major role in electoral politics. When Bearden was a teenager, she was elected President of The National Colored Women’s Democratic League in 1924. That role tasked his mother with the responsibility of registering Black women to vote and, in general, to get out the vote for the democratic party. The NCWDL’s efforts, in part, were responsible for shifting Black political loyalties from the Republican to the democratic party, ensuring a major electoral victory for the party of the New Deal. Bessye’s efforts were rewarded with an invitation to the White House from Eleanor Roosevelt.

His mother’s activism extended far beyond presidential politics. She was a cultural arbiter in Harlem and filled her home with like-minded cultural leaders and activists alike: W. E. B. DuBois, who co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or the NAACP, and who was the fiery editor of its official publication, Crisis; Black nationalist, Marcus Garvey; A. Philip Randolph, powerful labor activist, who decades later was a principle organizer for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom; James Weldon Johnson, WHAT as mentioned, an organizer of the 1917 Silent Protest; not to mention musicians, like Fats Waller, artists like Aaron Douglas, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes and many others were all guests at Bessye’s salons. Bessye, herself, held a number of jobs that placed her at the heart of Harlem’s political and social scene. She had been a ticket-taker at Harlem’s immensely popular, Lafayette Theater, correspondent for the Chicago Defender and eventually Deputy Tax Collector. . Their activism had a set of clear goals: achieve full rights of citizenship, economic equity and, unabashedly, real political power.

Like his mother and her circle of famous friends, Bearden, as a college student, seemed intent on bucking the status quo, that is the established cultural norms which he believed inhibited the Black artist’s freedom and independence. In his first published essay on art, the 1934 essay “The Negro Artist and Modern Art,” while still a college student, he lambasts a major white patron of Black artists, the Harmon Foundation and critiques Black artists for producing timid work.[vii] He counsels Black artists to boldly paint the day-to-day realities of Black life in the manner of the Mexican muralists whom he admired. In other words, the content of Black artists should be unapologetically political.

It’s no surprise, that he began his artistic career as a political cartoonist. His interest in cartooning started as early as his freshman year at Lincoln University, at the start of the Great Depression. Bearden transferred to Boston University, where he drew cartoons for the student humor publication, even as he briefly contemplated a career in Major League Baseball. Transferring, once again, he completed his undergraduate studies at New York University, continuing to draw humorous cartoons for the student publication. By his senior year, however, he was publishing serious political cartoons for major Black periodicals.

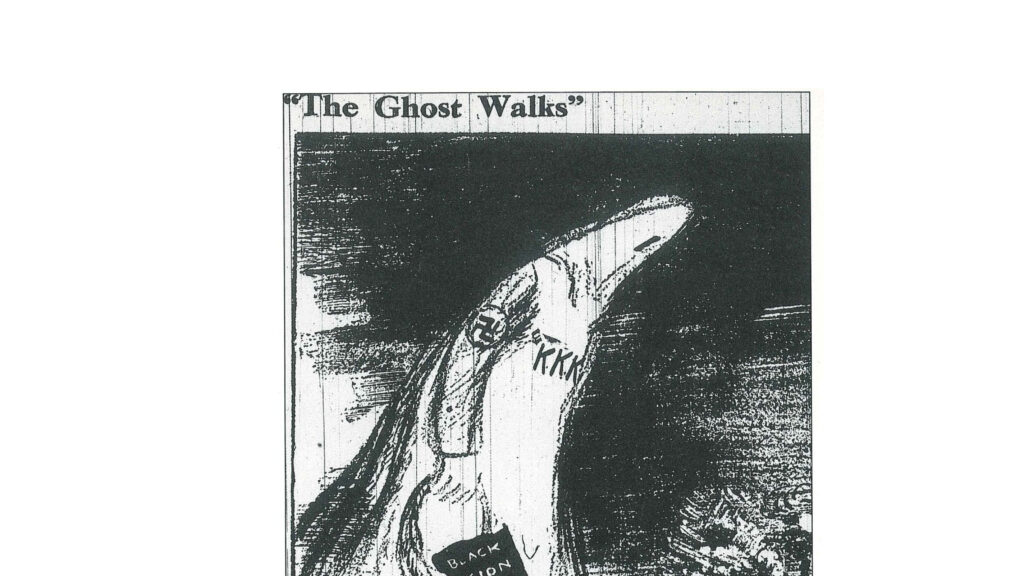

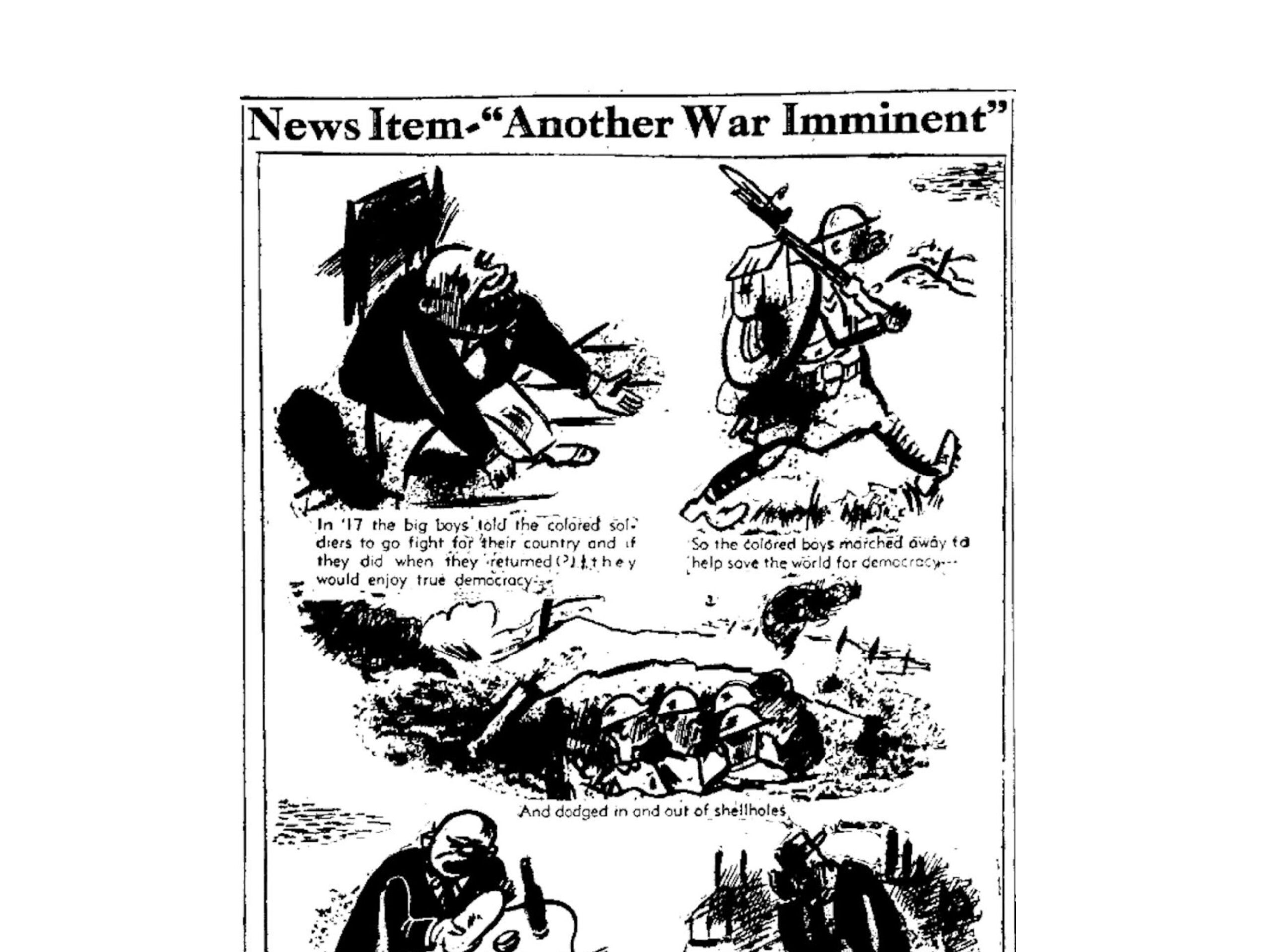

After graduation, when he became a caseworker for New York City government, (a full-time job he would hold for the next 30 years), he started producing weekly cartoons for the Baltimore African American, among other publications.Bearden’s seriousness about his cartoons is evident by the fact that, while he was still in college and after he graduated, he sought out German satirist, George Grosz at the Art Students League. Grosz’s cartoons had earned him the enmity of the Nazis and by the time he emigrated to the United States, he had given up cartooning and offered Bearden the advice of studying the work of the great masters of the past. It was advice that Bearden took to heart. Bearden’s career as a political cartoonist extended from 1934–38, during which he drew bold weekly cartoons for the Baltimore Afro-American. Examples include The Ghost Walks, 1936, and News Item: Another War Imminent, 1936(figure 11–12). During this period, Bearden, seeking to become recognized as an advocate for a growing labor movement, wrote articles for the Black press on the plight of Black steel workers.[viii] By 1938, he was painting scenes of hardship endured by Black laborers and their families.

A model of community activism as influential as his mother’s activities during the Depression, was the community organizing of Harlem artists. Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage were but two of the Harlem artist activists who helped create a real community of artists. The two organized the Harlem Artists Guild, an organization that Bearden joined as a young artist and where he was introduced to dozens of other Black artists. Initially led by Douglas and Savage, they lobbied—successfully—for financial support for Black artists in the form of increased participation for Black artists on WPA easel projects and mural commissions. They also fought for and won support for a WPA supported community art center in Harlem, what Bearden considered the first Black art museum in Harlem. Though it was short-lived, countless Black artists either taught or were trained there. World class artists such as Charles Alston, Robert Blackburn, Norman Lewis, Jacob Lawrence, Gordon Parks, Gwendolyn Bennett, and many others benefited in one way or another from the activism that garnered more federal support for Black artists.

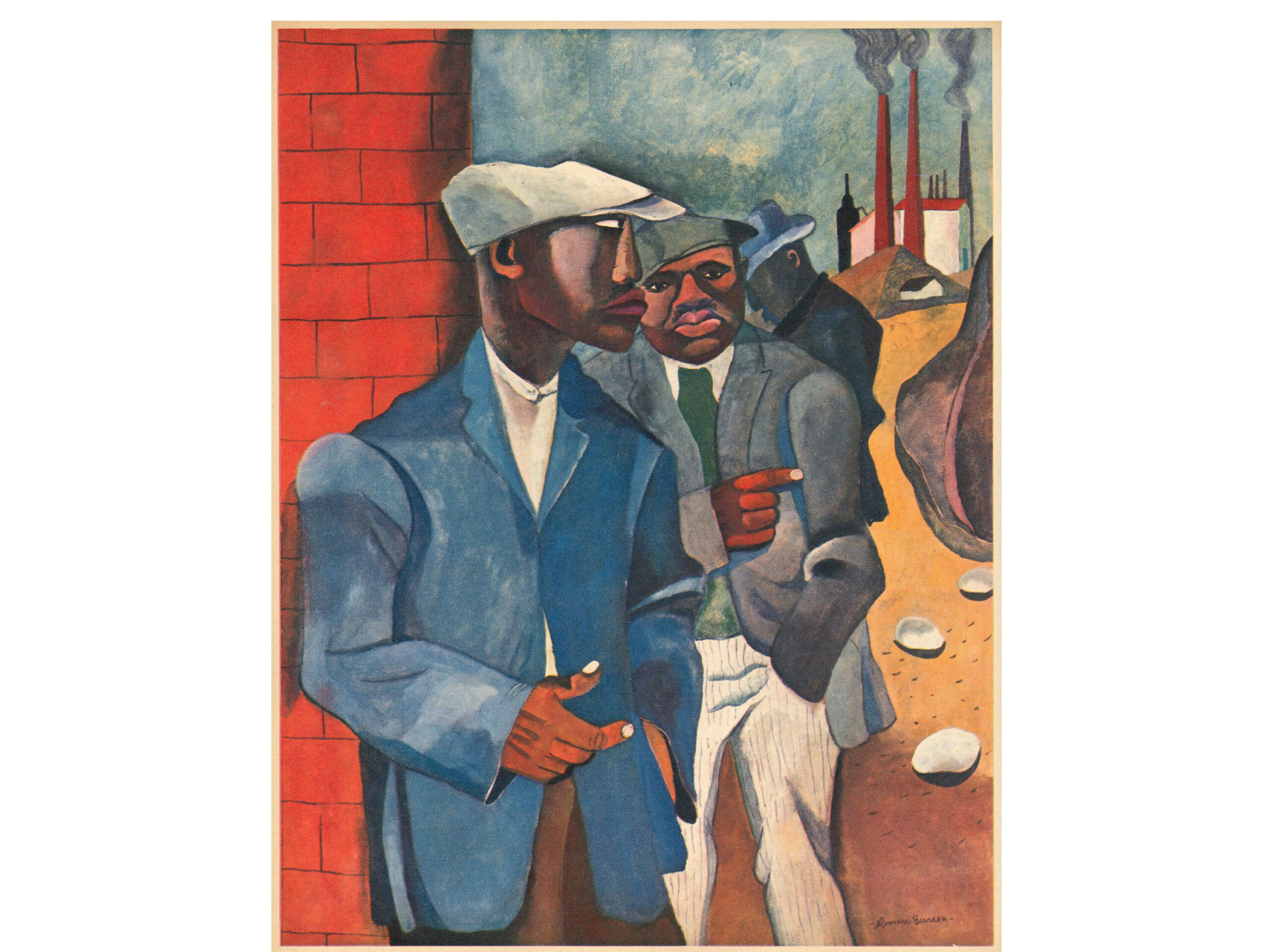

What I find striking about the 1930s is that in addition to lobbying for their fair share of federal largesse, Harlem artists took matters into their own hands and exercised “A politics of care.” A prime example was Savage, a superb sculptor, who studied at Cooper Union and in Paris and completed a commission for the 1939 World’s Fair (which was destroyed), She single handedly started the Art Garage., where Bearden recalls attending with Norman Lewis and Jacob Lawrence. In fact, it was Savage who made sure that Lawrence was signed up to benefit from the WPA easel program, support that led to some of his extraordinary early work. Bearden’s cousin, Charles Alston, a painter, and James Lesesne Wells, a master printmaker, conducted art courses at Utopia House, a workshop that provided early instruction to a young Jacob Lawrence. The workshop was hosted at the 135thStreet Public Library, run by the legendary Arthur Schomburg, who methodically collected and preserved invaluable primary reference material on the African diaspora. Schomburg, like “Professor” Charles Seiffert, who hosted seminars on Black history, took it upon himself to organize a group of artists, including Bearden and Lawrence, to view MoMA’s 1935 exhibition African Negro Art. Alston later went on to co-found “306,” an arts collective located at 306 west 141st Street. It was the 306 group that mounted Bearden’s first solo exhibition of paintings completed between 1938 and 1941. The paintings focused on the hardships of everyday life, the large bulky figures painted in a style that reflected his love of artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and lessons learned in the studio of George Grosz (figure 13–14).

With the onset of WWII, the WPA weakened and finally disbanded and with it an important source of financial support. After the war, the political environment in this country was chilled by the onset of the Cold War. National suspicions about lurking communists manifest most dramatically during the hearings of House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), launched before WWII, and the McCarthy hearings, which began after the war. After Bearden’s discharge, he found Harlem a changed place. While he was in the Army, his activist mother died. Artists left Harlem. Federal funding was dissipated and disappeared. Bearden found himself as a mid-career artist without the community that had surrounded him like a nourishing cocoon in his early years. With the loss of that community, for nearly two decades, his public political voice was quieted. In 1946, he wrote one major essay. That essay, The Negro Artist’s Dilemma, is a complete shift from his point of view about race and art before the war.[ix] He rejects the label of Negro Artist and argues, instead that, “The Negro artist, must come to think of himself not primarily as a Negro artist, but as an artist. Only in this way will he acquire the stature which is the component of every good artist.”

Bearden’s activism might have quieted but public political activism around issues of race and equity did not. Harlem residents Thurgood Marshall, Mollie Moon, and Adam Clayton Powell were amassing organizing power in the 1950s that would blossom in the 1960s and 1970s. Marshall’s successful Supreme Court cases that challenged Jim Crow laws as unconstitutional reached a zenith in 1954 with his successful argument of Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall’s win against segregated public schools implied the de-segregation of all public spaces, an implication tested a year later by the landmark Montgomery Bus Boycott. Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat was followed by a surge of other protests. Lunch Counter sit-ins, for example, organized by students at North Carolina AT&T spread to tens of thousands of students who participated in similar protests at other Historically Black Colleges and Universities in the South. Buses traveled from the North to the South in the early 1960s, filled with Black and white passengers, whose purpose was to join grass roots efforts to register disenfranchised Black voters in the South. Despite the activism in his own neighborhood and around the country, Bearden was disengaged. Surrounded by political activism he chose to spend almost two decades, the years between the end of WW II and the March on Washington, on what he would call a “Voyage of Discovery.”[x]

His words make me think that there may be a politics of becoming. In our hyper-accelerated contemporary world of texts and tweets, I wonder if artists are able to take the necessary time and space to disengage. If an artist wanted to undertake a voyage of discovery, what do they do, where do they go? Is there a place where they can take risks, make mistakes, fail, and in the words of Samuel Beckett, fail again, fail better? The nearly two decades of Bearden’s mid-career years enabled him to do just that. Unanticipated, perhaps unwanted, the time turned out to be absolutely necessary to this artistic evolution.

A Voyage of Discovery

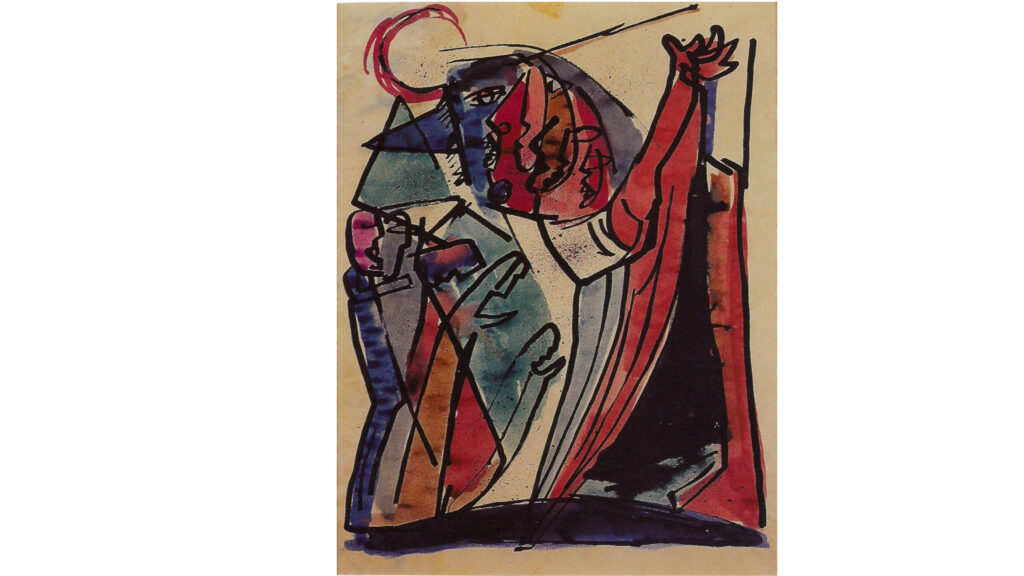

After the war, during this Voyage of Discovery, Bearden’s painting style undergoes abrupt shifts and changes. During the 1940s, Bearden paints cubist-inspired figurative abstractions, based on what he called “universal themes.” An example, his first series based on The Passion of Christ (figure 15).

This series won him a place, after the war, at a prestigious downtown gallery, The Samuel Kootz Gallery. As he exhibited with Kootz, he continued studying painting from the past. His pedagogical process was to make a photographic blow-up of masterworks and copy them. The influence of his self-taught practice is evident in work from this period. Most of Bearden’s artistic production from 1944 to 1950 is in the form of a series based on a single theme or literary work. One such scene is from a series, based on an elegy to a bullfighter defeated in the ring, written by the poet, Garcia Lorca (a former guest in Bessye Bearden’s home. The series is entitled, Lament for a Bullfighter (Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias). The scene, illustrated here, painted in a cubist-inspired style, in contrast to the social realism of his earlier work, is entitled, Death of Sanchez Mejias. Bearden’s reliance on a 14th century painting, Duccio’s Burial of Christ, (a detail from his fourteenth century Maesta altarpiece, Siena) is evident (figures 16–17). A reproduction of Duccio’s masterpiece is visible in photographs of his studio from that period. Years later he would reference the fourteenth-century painting in one of his few self-portraits. He has made use of the composition of the medieval work, not only to achieve compositional clarity but to make a comparison and emotional equivalence as well.

Right: Figure 17. Duccio di Buoninsegna, Entombment, 1308–11. Tempera on wood. Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena.

Bearden continued producing cubist-inspired watercolors and oils for the Kootz Gallery, at the time, considered one of the galleries that housed the new generation of American modernists: chief among them, Robert Motherwell and Adolph Gottlieb. A few years after the gallery engaged Bearden, they unexpectedly released him. Bearden discovered the brutal politics of the art world. Like most artists of that era, but especially women and artists of color, he was on his own. Bearden’s response was to take the opportunity to explore, geographically, as well as aesthetically. He took a leave from his caseworker job, sailed to Paris in the spring of 1950. As a World War II veteran, entitled to the G.I. Bill, he enrolled in a PhD program at the Sorbonne. The five months that he spent, ostensibly studying at the Sorbonne, he travelled all over Europe, visiting one masterpiece after another. He studied painting but did not actually paint himself. In Paris, he took the opportunity to visit Picasso and Leger in their studios, to assist the sculptor Brancusi, to listen to James Baldwin read an excerpt of his novel in progress, or to visit one of the many Parisian jazz clubs. The sense of freedom was exhilarating. He returned to his job in New York with the idea that he would find a way to go back to Paris. Still not able to paint, he briefly took up songwriting.

During these “discovery” years, he also struck up a correspondence with the abstract painter, Carl Holty. The two exchanged long letters about the nature of art. Some, written over several days, debated what is enduring and durable in art. The letters served as the notes for what would become their co-authored book, The Painters Mind: A Study of the Relations of Structure and Space in Painting. These conversations about form, composition and structure were essential to Bearden’s education as an artist and laid the foundation for his future work. Nonpolitical in nature, they were essential, nonetheless.

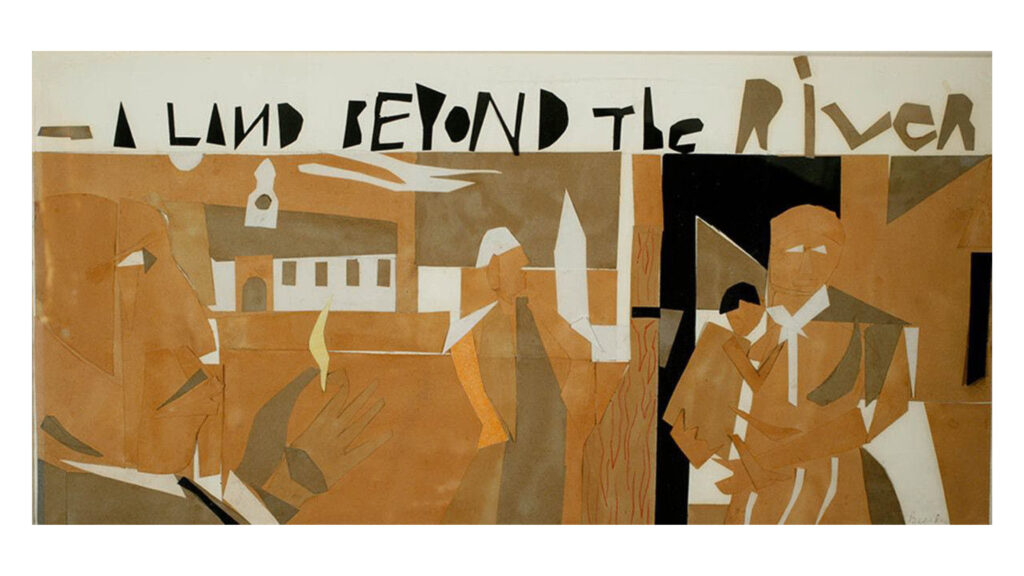

Songwriting, though moderately successful, was not Bearden’s métier, In 1954, he married Nanette Rohan, and with her gentle persuasion, returned to painting. His new work, large non-objective abstractions that he exhibited publicly with a new dealer, Cordier-Warren (figure 18) and which brought him modest critical success. Privately, he sketched and began to experiment with collage, such as his 1957 piece A Land Beyond the River, which he made as a gift to a playwright friend (figure 19).

Re-birth: The Prevalence of Ritual

It was the March on Washington, however, resonating with the grandeur and ambition of the public political demonstrations he had witnessed as a boy, that fully re-awakened his sense of political agency. A direct connection with his more politicized past sparked that awakening. A. Philip Randolph, an organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and former friend of his mother’s, called Bearden and asked him to organize a group of artists to join the March. Bearden complied. The group of artists that he and other Black artists assembled would be the essential catalyst for his shift to his mature work, the third and final phase of his artistic career and the most politically effective. A month before the march, on July 5, 1963, Bearden, with the assistance of several other Black artists, gathered a group of Black artists in his Chinatown loft. According to minutes from the meeting, their mission was to discuss “the commitment of the Negro artist in the present struggle for civil liberties” and “to discuss common aesthetic problems.” They called their group, “Spiral,” and eventually included fifteen artists, fourteen men and one woman. Together, they represented just about every point of view on what it meant to be Black and an artist, and they enjoyed the luxury of debating their differences openly. Most importantly, their convocation represented the re-convening of a collective that reminded Bearden of the artist communities of his past.

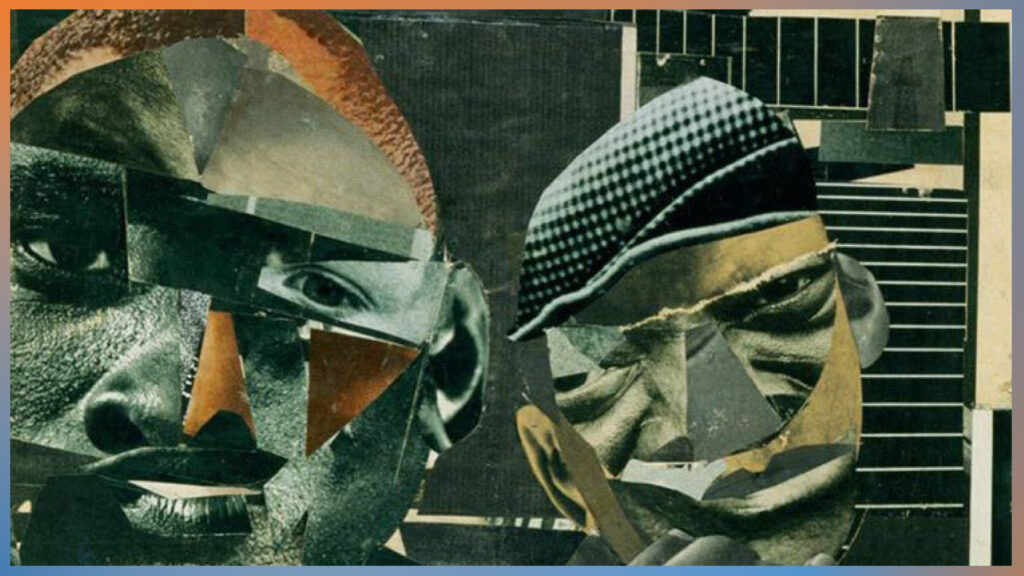

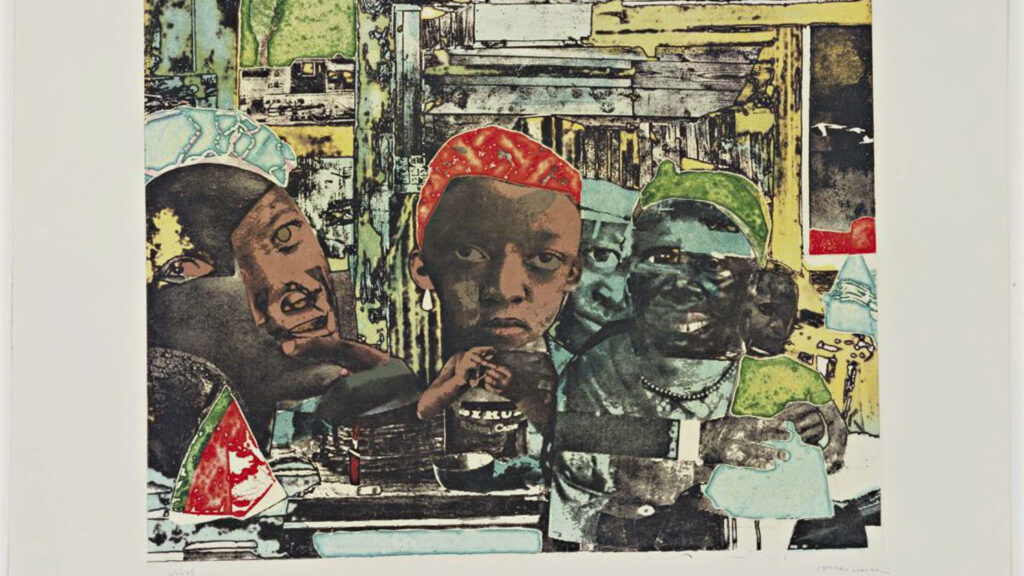

Shortly after the founding of Spiral Bearden attempted to interest the members in a group collage project. He brought a brown bag full of photographs he had cut from fashion magazines, Jet and Ebony, from magazines on African Art and other assorted illustrations. His Spiral colleagues were not interested, but Bearden privately continued to develop works using the scraps and fragments he had been clipping and saving. A Spiral colleague, Reginald Gammon, saw some of the small collages and suggested that Bearden make a black-and-white photostatic blow-up of the small works to make what would become the billboard size Projections. In the fall of 1964, Bearden’s gallery, Cordier-Ekstrom, mounted an exhibition filled with both collages and Projections entitled, Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual (figure 20).

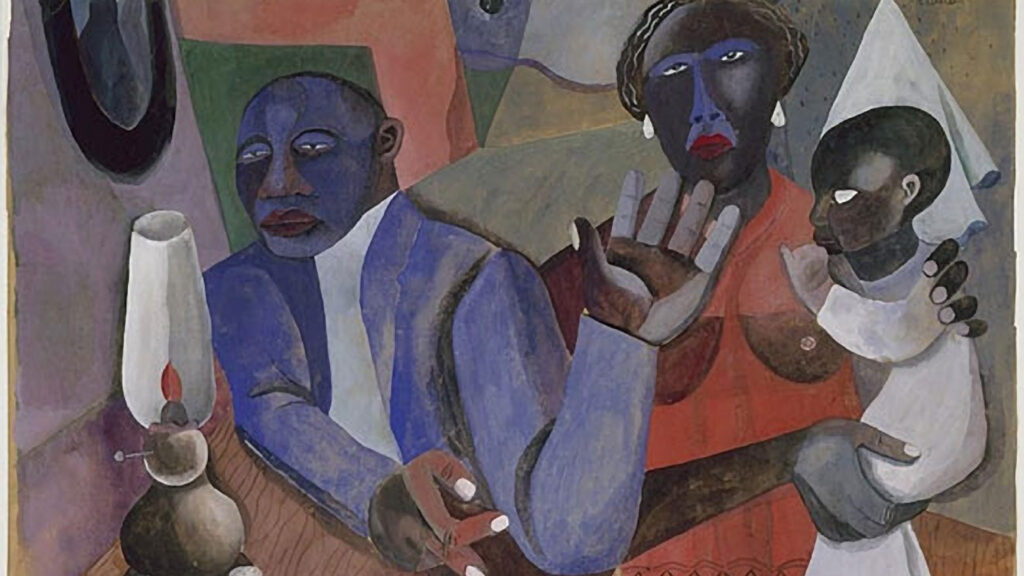

Novelist Ralph Ellison describes Bearden’s collages best when he states that his method was identical to his meaning and that the artist was able to represent “leaps in consciousness, distortions, paradoxes, reversals, telescoping of time and surreal blending of styles, values, hopes and dreams which characterize much of Negro American history.”[xi] Asserting Black identity in this way defied simple categorizations, laid claim to a multitude of heritages and asserted the right of self-definition. A work from the In Common exhibition illustrates Ellison perspective, The Evening Meal of Prophet Peterson, 1964 (figure 21). Even as we experience the clash and disruption of multiple cultural references, we understand the tableau as the enduring ritual of a celebratory family meal.

Bearden’s return to the representation of the life and culture of his people in all of its complexity was accompanied by return to even more intense political activity. Institutional politics were critical: he served as artistic director of the Harlem Cultural Council, and, as noted, sat on the advisory board of the Studio Museum, served as a trustee of Bob Blackburn’s printmaking workshop, co-founded and co-directed Cinque Gallery, along with his artist buddies, Norman Lewis and Ernest Crichlow, and was a member of the New York State Council on the Arts, one of the earliest post-war public funding agencies. By all accounts, Bearden was an active and vocal member of NYSCA, standing up for artists whom he thought had been overlooked and quick to critique institutions he found wanting in their cultural inclusiveness. He participated in protests against the Metropolitan Museum’s Harlem on My Mind exhibition, organized by artist Benny Andrews as head of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) and the Whitney Museum. And he insisted, as we know, that a retrospective of his work end its national tour in Harlem. In the last two decades of his life, however, Bearden began to step outside of this intensely activist life with increasing frequency. The island of St. Martin, home to his wife’s family, where he and Nanette built a home, re-connecting to a spirit of ancestry and origins, became a safe harbor, a place of regeneration. .

Bearden’s political influence impacted me personally in many ways. A few years after seeing the retrospective, I received my first curatorial assignment at a major museum: to curate a show of Bearden’s work. Mysteries: Women in the Art of Romare Bearden, opened at the Everson Museum in Syracuse New York in 1975, accompanied by a slender catalogue with my first exhibition essay.[xii] To my surprise, Mr. Bearden and his wife, Nanette, attended the opening, driven by a collector with works in the show, and Bearden and Nanette’s good friends, the playwright Barrie Stavis and his wife, Bernice.

Shortly after the Everson show, my husband and I, still in graduate school, decided to acquire one of Bearden’s prints. Printmaking was the artist’s way of making his original artwork affordable, in this case to two, impoverished graduate students. Shortly after the exhibition, we travelled to New York and bought The Train, 1975 (figure 22), an etching and aquatint, with hand coloring, #10 of an edition of twenty-five, measuring, 21 by 20 ¼ inches. Having received an unexpected financial gift, we decided that owning the print was more important than buying a television set (which we did not yet own), and it was a political choice as well. Owning that print was not really an economic choice. The women in that print have become part of my psyche, my world.

Looking at them, I am reminded of a character from the work of the late great, Toni Morrison, Baby Suggs. Baby Suggs was the un-ordained preacher who, in the novel Beloved, delivers a sermon in the clearing to the Black men, women, and children of in the area where she lived.[xiii] I look at the faces staring at me, I see the creative potency of the oversized hands that Bearden has given them. I hear the words of Baby Suggs, in the Morrison’s novel delivering the Sermon in the Clearing.

“Here,” … “in this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in the grass. Love it. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh. They despise it. They don’t love your eyes; they’d just as soon pick em out. No more do they love the skin on your back. Yonder they flay it. And O my people they do not love your hands. Those they only use, tie, bind, chop off and leave empty. Love your hands! Love them. Raise them up and kiss them. Touch others with them, pat them together, stroke them on your face ’cause they don’t love that either. You got to love it, you!

Baby Suggs goes on to say:

More than eyes or feet. More than lungs that have yet to draw free air. More than your life-holding womb and your life-giving private parts, hear me now, love your heart. For this is the prize.”

Perhaps the greatest political legacy that Bearden and the artists who work in the sunlight of his legacy have given us is the freedom of our imagination, our ability to possess an open and inviting heart, an unassailable self-love. When all is said and done, in the words of Baby Suggs, “this is the prize.”

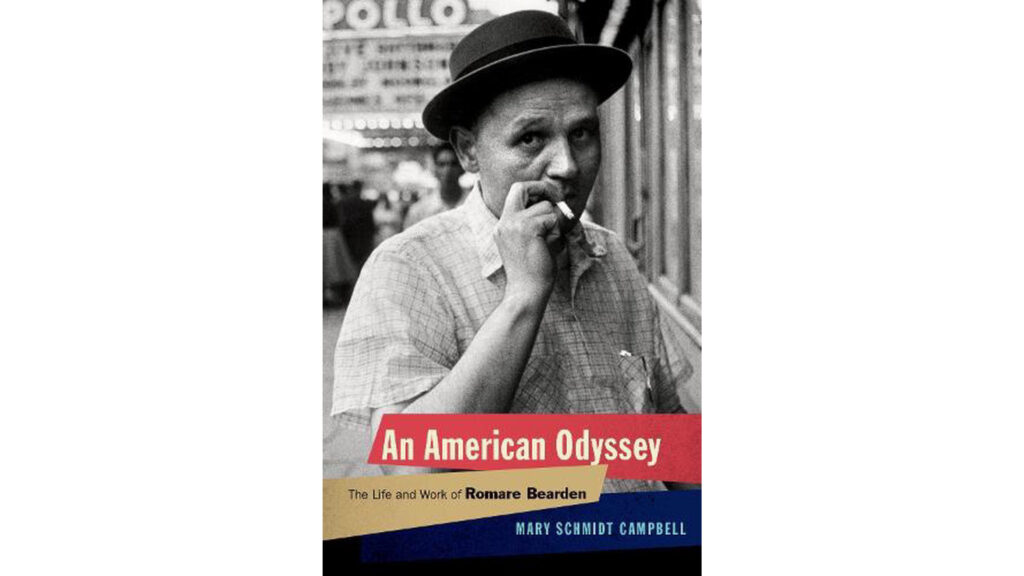

[i] This essay relies on research completed for a definitive biography of Romare Bearden: Mary Schmidt Campbell, American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[ii] Susan E. Cahan, Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, “Romare Bearden and the Prevalence of Ritual and the Sculpture of Richard Hunt at the Museum of Modern Art, pp. 171-252, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2015). Cahan provides a detailed account of the protests, the history of exhibitions of African American artists at MoMA and the role of Tom Lloyd and Faith Ringgold in securing exhibitions for Hunt and Bearden.

[iii] The institutions involved in both the exhibition and the symposium are as follows: The Institute of Race, Power, and Political Economy at the New School; The Romare Bearden Foundation; The Vera List Center for Art and Politics at the New School; and the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University, Newark. Special thanks to Henry J. Ramos, Senior Fellow, The Institute on Race, Power, and Political Economy, who spearheaded the project and my long-time colleagues, Diedra Harris-Kelley and Johanne Bryant-Reid, co-directors of the Romare Bearden Foundation.

[v] “The power of the parade consisted in its being not a mere argument in words, but a demonstration to the sight.” James Weldon Johnson, “An Army with Banners,” The New York Age, August 3, 1917, reprinted in Sondra Kathryn Wilson, editor, The Selected Writings of James Weldon Johnson, Volume I: New York Age Editorials (1914-1923) (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

[vi] New York Times, ‘Fifth Ave. Cheers Negro Veterans,” February 18, 1919, I p. 6.

[vii] Romare Bearden, “The Negro Artist and Modern Art,” Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, 12 (December, 1934), 371-372.

[viii] Bearden, “They Make Steel: Worker’s Life Drab and Dark without Union,” New York Amsterdam News, October 23, p. 13. See also Bearden, “ The Negro in Little Steel,” Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life 15 (December, 1937) 362-365,380.

[ix] Bearden, “The Negro Artist’s Dilemma,” Critique a Review of Contemporary Art I, no. 2 (November,1946) p. 22.

[x] Bearden uses this phrase in a letter to Harry Henderson, October 25, 1949, quoted in Campbell, An American Odyssey, p. 167.

[xi] Ralph Ellison, “ The Art of Romare Bearden,” Exhibition Catalogue, Art Gallery at the State University of New York at Albany, November 25- December 2, 1967.

[xii] Mary Schmidt Campbell, “Mysteries: Women in the Art of Romare Bearden,” Exhibition Catalogue, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York, 1975.

[xiii] Toni Morrison, Beloved, Vintage Classics, 2007.

All ART ©Romare Bearden Foundation, NY

Romare Bearden’s Art can be licensed through VAGA at ARS, NY info@arsny.com