By Sarah Drake, herARTS in Action, Sauk Rapids, MN

World-renowned collagist Romare Bearden has been my artistic muse for as long as I can remember. I grew up in the country, ten miles outside a small central Minnesota town without a stoplight and before the internet, so I don’t really know how I learned about this multi-talented Harlem Renaissance artist. His work has always just been known to me. Bearden’s artwork is central to my work, whether working as a teaching artist or creating art. I like to use his artwork because it appeals to people of all backgrounds. However, I especially appreciate the fact that, through Bearden’s eyes, Black people get to see themselves, their stories, and history respectfully reflected back to them and by a man who, in so many ways, shared their journey.

Romare Bearden’s collages, though beautiful, provide a powerful framework for understanding the intricate ways in which art, economics, politics, and race converge. I am constantly aware of the profound impact these intersections have on both personal and collective experiences. Bearden’s ability to weave together fragmented materials into cohesive, evocative pieces mirrors the ongoing effort to reconcile elements of our societal fabric. His work challenges us to confront and celebrate the complexities of identity and justice, inspiring a dialogue that transcends artistic boundaries. Bearden’s work reminds us that art not only captures the essence of our shared human experience, but it also serves as a catalyst for meaningful change and understanding in a world that is too often divided by its contrasts.

As a white woman, artist, humanitarian, and most importantly, a single mother to a biracial child, I find myself at a unique crossroads where art, racial justice, and representation intersect in deeply personal ways. I do the work that I do for my biracial daughter so that she can see herself positively represented in the world. This intersection of lived experiences shapes my worldview, my art, and my understanding of the challenges and responsibilities that come with being a parent to a child of mixed race.

My most recent art exhibition built on and was named after Bearden’s iconic 1979 collage work, The Conversation. People typically do not want to have conversations about hard topics, so that’s why I started using Bearden’s work in my teaching and artmaking. We are living in a time where education, books, and history are being banned—where our very prospects to succeed as an inclusive multiracial society are being seriously challenged. To address these realities, the exhibition, which also included works by my Black and African students, went beyond just identity and representation, precisely by urging our audience members to engage in difficult but essential conversations.

Participating in something of such magnitude with my artistic muse was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I had to persevere through a broken dominant wrist and a severely sprained non-dominant wrist after an accident just months before our opening. What I created, though, is my best work to date, and I feel there is a great metaphor in there of creating beauty in and from my brokenness.

Social Justice Art Activism

I was an artist growing up and wanted to be one when I grew up but, both at home and elsewhere in my rural community, my dream wasn’t supported as a realistic career choice. Many years later, I found my way back to the arts. I found myself trying to have difficult conversations with people on race and discrimination. My words failed me, but my artwork helped me connect with people. I created a series based on well-known artworks, but I tweaked each piece with a Black or African lens. People would say, “Oh that’s the Statue of Liberty or the Mona Lisa,” and then catch themselves and say, “Wait, what’s that?” And we would discuss enslavement and the shackles on the Statue of Liberty.

When I left the arts for many years, I had forgotten about the work of Bearden. When I started making collages again, I remembered his work. When I travel to New York, Washington, DC, or elsewhere, I will look up to see if his art is on view anywhere. I traveled to Utah in 2022 specifically to see a whole exhibition of just his work.

Collage as an artistic technique involves assembling diverse materials—such as paper, fabric, and photographs—into a cohesive whole. For Bearden, collage was not just a mechanical method of creative application, but also a means to convey complex narratives. His work often features fragmented images that come together to tell a story, mirroring the experiences of African American life and culture. He and I both cut and tear paper, use other materials in addition to paper, and highlight large hands. While Bearden’s depiction of hands highlights the labor of Black people in this country, I use them as a reminder that my hands help me create, but also that, owing to a debilitating physical condition that I face, I’m rapidly losing mobility and function in both.

For me, his technique speaks to the power of assembling elements to create a unified vision. His work resonates with my artistic practice, where I often blend materials and ideas to reflect the multifaceted nature of identity and experience. This technique also provides a powerful metaphor for navigating the complex intersections of race and identity in our personal and societal narratives. Through my work, I try to dismantle these barriers, creating pieces that challenge the viewer to see beyond skin color, beyond stereotypes, and into the complex, multifaceted identities that we all hold. I’m driven by a commitment to ensure that whatever art I produce not only represents my voice, but also the voices of those who are most marginalized.

As a collagist and more specifically, a Bearden fan, the piece you want to see in person is, The Block, because it’s not shown online or in books in its entirety or true colors. So when I was working in Washington, DC and The Block was on exhibit in New York, I made the four-hour trip to see it. I was weak in the knees and teary-eyed when I walked around the corner and saw this 18-foot piece. It inspired me to create a piece for The Conversation exhibition called, My Global Block. When I look at my block, or even city and region, I don’t feel supported or embraced in my social justice activism or artwork. To resonate with Bearden’s block experience, therefore, I needed to reach out to people in places far away from where I live and work, like New York City, Washington, DC, and the Western African nation of Burkina Faso.

The Art of Race

Bearden’s exploration of race and identity is central to his work. His collages often reflect the African American experience, capturing both the struggles and triumphs of these communities. By incorporating elements of African American culture, history, and daily life, Bearden’s art serves as a powerful reflection of and commentary on racial identity and the importance of acknowledging and celebrating diverse identities while addressing the systemic issues that impact these experiences. I find it particularly poignant as I navigate the complexities of raising a biracial daughter and being welcomed into Black and African communities while carrying the inherent privilege of being a white woman.

As a white artist engaged in these conversations, I grapple with the responsibility of contributing meaningfully without appropriating or overshadowing the experiences of BIPOC communities. In my work, I strive to create spaces where dialogue can occur (including the complexities of racial justice) and be explored with nuance and depth. Art can serve as a bridge, connecting people of different backgrounds and experiences, and fostering empathy and understanding. However, this bridge must be built carefully, ensuring that it does not become a one-way street where white voices dominate the narrative. This means it’s my job to listen, learn, and reflect, rather than lead. It means acknowledging the privilege that comes with my race and using it to support and uplift the work of BIPOC artists who are at the forefront of the fight for racial and economic justice. It means creating art that not only challenges my audience, but that also challenges me, pushing me to confront uncomfortable truths about the society we live in and my place within it.

Representation in art is not just about visibility; it’s about authenticity. As a mother and teacher, I am deeply invested in the way BIPOC individuals are portrayed in art and media. Too often, these representations are limited, stereotyped, or tokenistic, reducing complex identities to simplistic caricatures. This not only perpetuates harmful stereotypes but also erases the richness and diversity of BIPOC experiences.

In my art, I strive to create works that reflect the full spectrum of the human experience. This involves collaborating with BIPOC artists, scholars, and community members to ensure that the stories entrusted to me to share are informed by those who live them. It also involves being open to critique and being willing to make changes when I get it wrong—a crucial part of the ongoing process of learning and unlearning. As an artist, I must contribute to a broader cultural landscape where BIPOC individuals are represented with the dignity and complexity they deserve.

One of the most challenging aspects of being an artist engaged in racial and economic justice work is balancing artistic freedom with social responsibility. Art is, by nature, an expression of the self, a form of creative exploration that often resists boundaries. However, when engaging with issues of race and inequality, this freedom must be tempered with a sense of responsibility toward the communities we depict. For me, this means being mindful of the power dynamics at play in my work. It means questioning whether my art is contributing to the conversation in a meaningful way or if it is merely replicating the same structures of oppression that I seek to dismantle. It means being willing to step back and let others take the lead, recognizing that my voice is not always the one that needs to be heard.

This balancing act is difficult, and I don’t always get it right. I consulted many people when working on the illustrations for my first book. Many talked about the stereotypical depiction of Black people in our culture as angry or mad and desired a clean slate with no facial features so they could be reimagined. So I made heads with hair, but there were no facial features. Literal, clean slate. But some people said I still got it wrong because I erased them. They asked where the features were that fully express them. This is a necessary part of the process, one which I embrace fully as both an artist and a mother. It is a reminder that art is not created in a vacuum but, rather, is deeply connected to the world around us—a world that is still grappling with issues of race, justice, and equality.

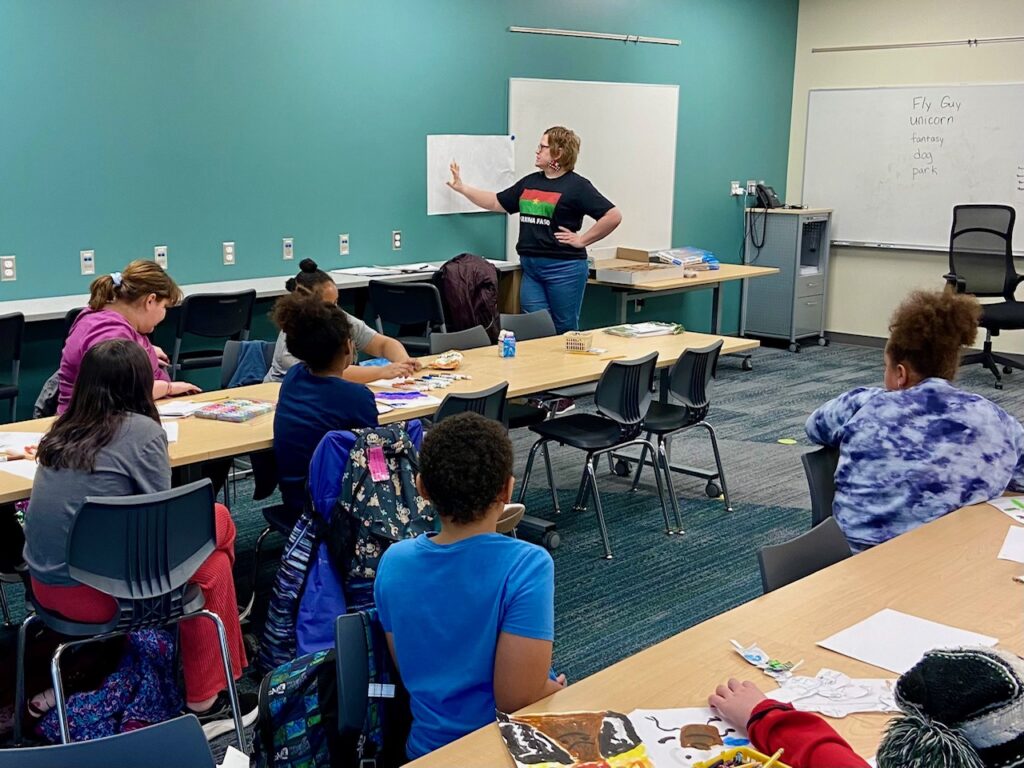

When I started to think about Bearden’s The Conversation and the important talks I was having or trying to have around my exhibition and in my ongoing practice, I thought about the kids I work with in the US and Burkina Faso. In Minnesota, we have some of the best educational test scores in the nation, if you’re white. If you’re a student of color, however, the results are the opposite. BIPOC children, parents, and community members have ideas, but they are typically disregarded by the status quo. The children have important things to say, but most adults aren’t listening. The children in my piece Listen to the Children are inspired by real people and sites where I do arts programming. Elements of the work get at the question: how are BIPOC children supposed to do well in school when they are fighting for life and respect for their very existence, and otherwise facing the lasting effects of institutionalized racism at every turn?

Collaging the Economics

The intersection of art and economics is a multifaceted space. For many artists, especially those from marginalized communities, economic barriers can significantly impact their ability to produce and share their work. Bearden’s career was marked by both success and struggle in this regard. While he achieved recognition and success later in life, his early career was fraught with financial difficulties. This economic struggle is a common narrative for many artists, particularly those outside the dominant cultural mainstream. I was told I was not a “real” artist by my local community because I didn’t go to art school and because I often sourced from found objects and otherwise repurposed items. As a single mom without child support or government assistance, I was the starving artist stereotype. Reusing materials was on brand as I cared about the environment, but I had to use what I could afford if I wanted to make art.

Bearden’s use of everyday materials in his collages can be seen as a commentary on economic realities. By incorporating scraps from magazines and newspapers, Bearden not only democratizes the artistic process but also reflects the conditions of his time. His work underscores the idea that art does not exist in a vacuum but is deeply intertwined with the economic realities of the artist and the broader community.

As an artist and humanitarian, I’ve experienced how economic factors influence access to artistic opportunities and resources. This awareness shapes my approach to creating art and supporting others in their creative endeavors. Because I am a white person, I must give credit to the people who are inspiring my artwork, but also ensure that I give money back to people and communities of color that I have worked with and who have far greater needs in the scheme of things than I do.

Anything I make and sell that is inspired by my many influences and contacts in Burkina Faso benefits the programming of herARTS in Action, a nonprofit I founded with the mission to create an equitable world through increased access and social justice with art in the US and Africa. If I use art in my class, even though it’s freely available on the Internet, I donate to the artist or organization of their choice. When I mentor students and they work with me on murals, for example, I pay them a stipend. Even though they are learning, they are helping me with a job that I get paid for, so they need to take part in the benefits also.

When I first saw Bearden’s Late Afternoon, it took my breath away. My mouth was ajar, and my hand was on my chest. I went too long without breathing because the security guard asked if I was ok. The colors and composition drew me in and wouldn’t let me go. On top of that, the piece reminded me of summers at my grandparent’s house. My family didn’t come from money, they lived in the country, and I remember family members getting indoor plumbing and telephones for the first time. The activities in Late Afternoon showed that Bearden’s lived experiences in the early 1900s US South were similar to mine in the late 1900s in Minnesota. I created Four Generation Afternoon, inspired by Late Afternoon, to honor family, ancestry, history, and the conversations that we need to have to move racial and economic justice forward.

Piecing Together the Politics

Bearden’s collages are also imbued with political significance. His work addresses racial injustice, social inequality, and political struggle. Imagery in his collages is a powerful metaphor for the fractured yet resilient nature of the communities depicted. For Bearden, his art was a means to engage with and critique the sociopolitical landscape of his time. His work reflects a deep engagement with the struggles of the African American community and serves as a call for social change and awareness. Bearden’s art provides a framework for understanding and navigating these intersections, offering insights into the political dimensions of racial and cultural experiences. His work challenges us to confront the sociopolitical realities faced by marginalized communities and inspires us to advocate for justice and equity.

Raising a biracial daughter in the state where George Floyd was murdered by the police, I am particularly attuned to how politics intersects with race and identity. His murder happened just an hour away from where I live and work, and was the first instance of police brutality on a person of color so close to home that my daughter could truly understand. She realized that could have been her. She created a piece of art that expressed her feelings, emotions, and thoughts about what was happening around her, and in the neighborhood where she was about to move to for college. I was curating a group show at a local business and because the artwork had a gun and police in it, they didn’t feel it would be well-received by the patrons. As an artist, it sucks to be censored, but my daughter somewhat understood that the piece was too political for a business that serves everyone.

However, a white girl about the same age, painted portraits of famous Black people, and she was allowed to exhibit them. My daughter’s understanding went out the window. She wondered why her voice was suppressed, but the white girl got to be seen, heard, and make money off of people who look like her. Now, the proliferation of post-George Floyd DEI efforts are over, nearly as quickly as they started. This is why I don’t make statements and promises based on the catastrophe of the day. I put my artwork into action, and if I’m not doing that, I want people to call me out. herARTS in Action was a very intentional name for my nonprofit.

Making art is a political act, especially for a woman, a person with disabilities, and a person who speaks out for the marginalized. The first time I saw Bearden’s Artist with Painting and Model was at the In Common symposium. It inspired my piece, Artist with Students, based on the students I work with in the US and Burkina Faso for access to clean water, sanitation, education, health, and art. As I created this piece, I thought about all the conversations I’ve had with gatekeepers in the development world. I’m seen as “just” an artist or underestimated because my budget isn’t at least half a million dollars, so I can’t access program funding.

Gluing it All Together

Romare Bearden’s legacy continues to influence the art world and discussions on race, identity, and social justice nearly 40 years after his death. His innovative approach to collage and his engagement with sociopolitical issues have left a lasting mark on the world. Bearden’s work challenges us to think critically about the intersections of art, economics, politics, and race and consider how these factors shape our understanding of identity and justice. His art remains relevant as we continue to grapple with issues of race, inequality, and representation.

As a white artist and humanitarian raising a biracial daughter, Bearden’s legacy inspires me to continue exploring the intersections of art and identity in my work. His innovative use of collage and his commitment to addressing societal issues provide a powerful example of how art can be a catalyst for change. His legacy continues to inspire and inform the transformative power of art in shaping our understanding of the world and advocating for justice and equity. Through my artistic practice and advocacy, I honor Bearden’s legacy by engaging with these critical issues and working toward a more equitable and inclusive society. I am creating understanding, building bridges, and striving for the world my daughter and people who look like her deserve.

________________________

Sarah Drake, MS, is an award-winning collagist, author-illustrator, and teaching artist in Sauk Rapids, Minnesota. She has a Master of Science degree in Social Responsibility from St. Cloud State University. Drake is the founder and CEO of herARTS in Action, an international nonprofit whose mission is to create an equitable world through increased access and social justice with art. Her work on human rights and social justice topics over the past two decades inspires her artistic creations.